A Study for the Ages

Seed banking is promoted as an amazing conservation tool, in part, because of the impressive longevity of stored seed. Stories of successful germination give great hope, including a 2,000-year-old Judean date discovered in an archaeological site and a 30,000-year-old Silene dug out of Siberian permafrost. We know now that such extreme longevity is not a trait of every species. And it wasn’t long ago that the longevity itself was in question.

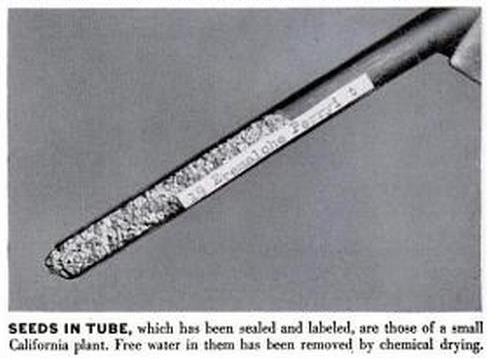

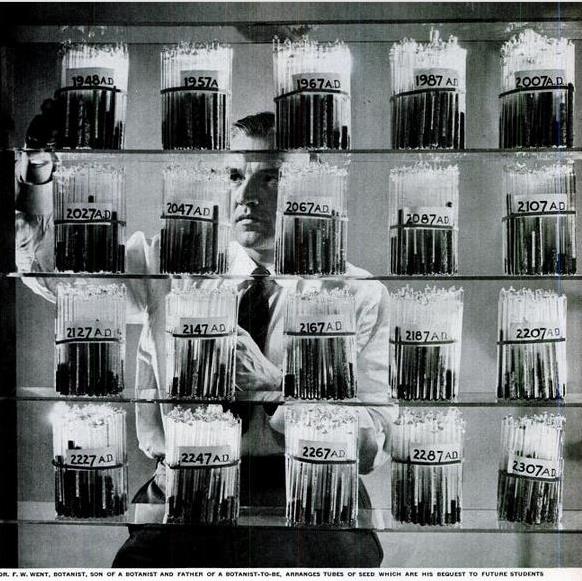

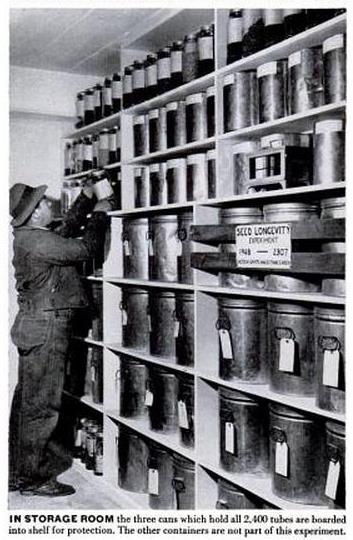

Claims of seed longevity were largely anecdotal in 1947, when Dr. Frits Went, a botanist at California Institute of Technology, and Dr. Phillip Munz, director of Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden (RSABG, and currently called California Botanic Garden), began an ambitious research project designed to last 360 years. Went used seed provided by RSABG staff, including P.C. Everett to conduct one of the first studies examining long-term storage of seeds maintained in partial vacuum. Seeds from 91 native California plants were vacuum-sealed in glass tubes, and sets of 20 tubes in metal cans were stored in a relatively climate-stable room at RSABG. Ideally, one set of seed would be opened after the first year, then with 10 year spacing and finally, every 20 years through 2307 as outlined in Went and Munz’s original paper.

The initial germination tests were conducted in 1948, 1957, and 1967 as planned. When the time came for the 1987 test, the director reported that the seed was missing. Just a few years later, in 1990, the RSABG endangered species coordinator Orlando Mistretta found the seed as he moved the RSABG seed entire collection to a new facility. Following the request of Dr. Went, the seed and the study were transferred to the National Laboratory for Genetic Resources Preservation (NLGRP) in Fort Collins, Colorado. In 1997, University of Northern Colorado master’s student Teri Christensen worked with NLGRP to pry open the containers of 50year-old seed and resume testing. In 2007, Rancho Santa Ana sent their seed bank manager at the time, Evan Meyer, to work with NLGRP staff to examine the seed originating from his garden.

The results have been mixed, yet intriguing.

Seed conserved in the study continues to germinate–unsurprisingly, at a declining rate. Although the seed banking community now follows low humidity, low temperature storage protocols, vacuum storage appears to have been relatively effective, with well over half the species continuing to have germination after 50 years. In general, the results of this study focused on California natives mirror those of other long-term seed experiments focused on economically or culturally important species.

-

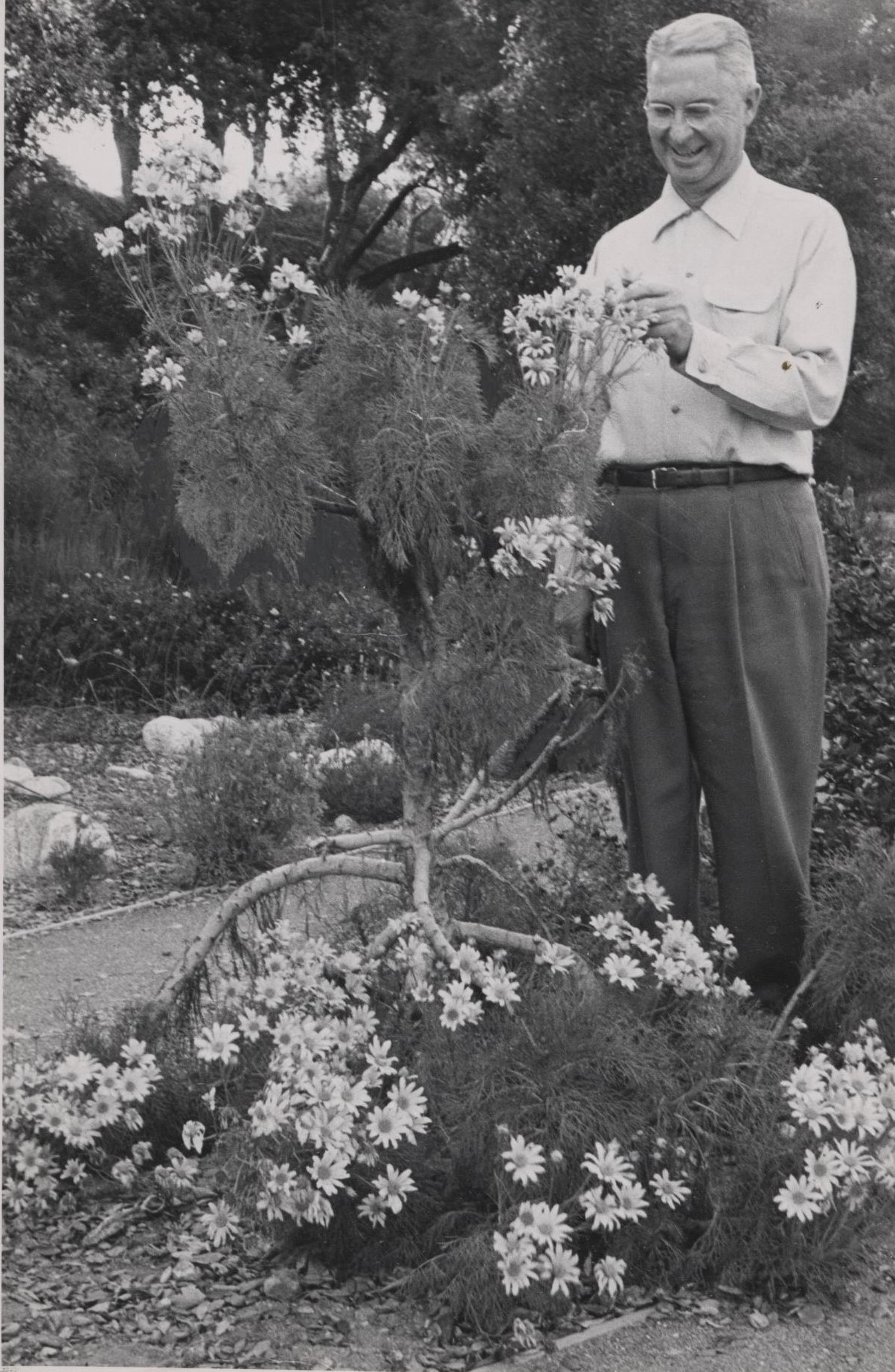

In the 70 years since Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden contributed Coreopsis maritima seed, both have undergone name changes! A collection made now would have California Botanic Garden collecting Leptosyne maritima. Photo by Joe Davitt courtesy of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. -

Deer weed (Acmispon glaber) seed collected for the study has had low germination across all tests - possibly pointing to seed quality or dormancy issues. Photo courtesy of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance. -

Most of the 91 species were annuals or other herbaceous plants, but the study also included a few shrubs, such as California buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciulatum). Photo courtesy of San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance.

Went’s experiment included 91 species from several families and habitat types, allowing for some analyses of basic traits that could influence seed longevity or germination issues such as dormancy. The primrose family (Onagracea) retained higher germination than the sunflower family (Asteraceae). Woodland seeds flourished when compared to desert species. Building on this and similar studies, we understand that traits, taxonomy, and habitats should also be examined when asking questions about seed longevity.