Ed Guerrant, Ph.D.,

The CPC family pays tribute to our friend and colleague Ed O. Guerrant, Jr. as he embarks on his new adventures in retirement. Ed’s contributions toward refining our best practices for ex situ care and defining CPC values and ethics are part of his lifelong legacy to plant conservation. – Joyce Maschinski

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I can’t remember a time when I didn’t love the out of doors. Growing up in the suburbs east of Los Angeles in the 1950s, I spent a lot of time outdoors. We lived close to the mountains and had a family cabin in the San Bernardino Mountains. From the more intellectual side of things, I was a junior zoology major in college when I took a plant biogeography class. That did it, and I soon became a double major in Zoology and Botany. A two quarter plant taxonomy class with C. Leo ‘Hitchy’ Hitchcock sealed the deal.

What was your career path in becoming Director of the Rae Selling Berry Seed Bank and Conservation Program?

My career was more a result of a series of unpredictable events than any sort of intentional path. After I finished my PhD in Botany, I followed my girlfriend, later wife and mother of two wonderful children, and moved to Portland, OR. I taught biology, ecology, genetics and evolution as an adjunct at Lewis and Clark College from 1986 to 1990. The Berry Botanic Garden – a small 6-acre estate garden – was only a mile away from Lewis and Clark College and historically a faculty member sat on its board. The other two botanists had done it several times each, so I was recruited.

I joined the board at a tumultuous time for the Garden. We were transitioning between Executive Directors, with the new hire unable to change coasts for many months. During this time, my predecessor suddenly and unexpectedly resigned. Not surprisingly, the board was distressed. But I had what I thought would be the perfect solution: hire me.

Thrilled with the idea of working in plant conservation overall, I was initially skeptical about the practice of ex situ plant conservation: taking seeds out of nature to protect them in nature seemed sketchy. It was a question I thought about a lot, and along with others, this quest eventually led, at least indirectly, to the CPC book Ex Situ Plant Conservation: Supporting Species Survival in the Wild. The subtitle alludes to the solution: ex situ methods are not an end in themselves, but a means to an end.

The book you co-edited, Ex Situ Plant Conservation, provided a base and framework of the recently updated CPC guidelines. Can you tell us a little about how that book came about and the process of putting it together with your colleagues?

The idea for the book occurred at the 1996 CPC annual meeting, in Denver, CO, arising out of a conversation I had with Kay Havens and Carol Dawson. We perceived a need to fill the gap between collection and reintroduction that then existed in the first two CPC books. It grew from there, ultimately in the attempt to address storage, to complete the trilogy: collect, store, and if necessary, use. We also wanted to address broader strategic issues of how, in plant conservation overall, ex situ plant conservation fit into the larger scheme of things.

Carol was unable to continue, but Kay and I, feeling the need for an international perspective, invited Mike Maunder, then at Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, to join us.

One thing that I didn’t realize before we outlined the book, and the associated symposium at the Chicago Botanic Garden, was how creative an endeavor it is to edit a book. I had naively thought of it as simply editing chapters that other people wrote. I was pleasantly surprised to find a lot of creative opportunity in the conception and organization of the book, and the conference on which it was based. Island Press was wonderful to work with, and instilled in us the need for the book to cohere as a larger whole. They helped keep us grounded and moving forward.

What are a couple of the major threats/challenges facing rare plants in the Pacific Northwest? How has your/your institution’s work addressed them?

It depends on scale in time and space. In the near term, it is the regular suspects: habitat destruction, effects of invasive species.

In the longer term, and, like the high wispy cirrus clouds in an otherwise blue sky that announce the coming of a warm front, we are beginning to see the first wispy effects of global climate change in the increased intensity of extremes in temperature and precipitation. This realization led us at the seed bank to begin adding seeds of more common species to our ongoing efforts with rare species.

What about working with seeds/seed banking has surprised you?

Perhaps the most unexpected aspect of working with seeds and seed storage is the astonishingly diverse array metaphorical connections they have to so many aspects of life. It is not much of a stretch to think that agriculture as we know it could not have happened without some means of saving seeds for use in later years. Some have suggested that early community seed storage facilities in ancient Egypt might have contributed to the origin of currency, and the concept of credit, are based on them. Like money, a quantity of grain is fungible, making it and easier means of doing business than barter.

More broadly, I think Gary Paul Nabhan sums it up beautifully: “We need seeds because they are the physical manifestation of the concept we call hope.”

Please share one of your plant conservation success stories.

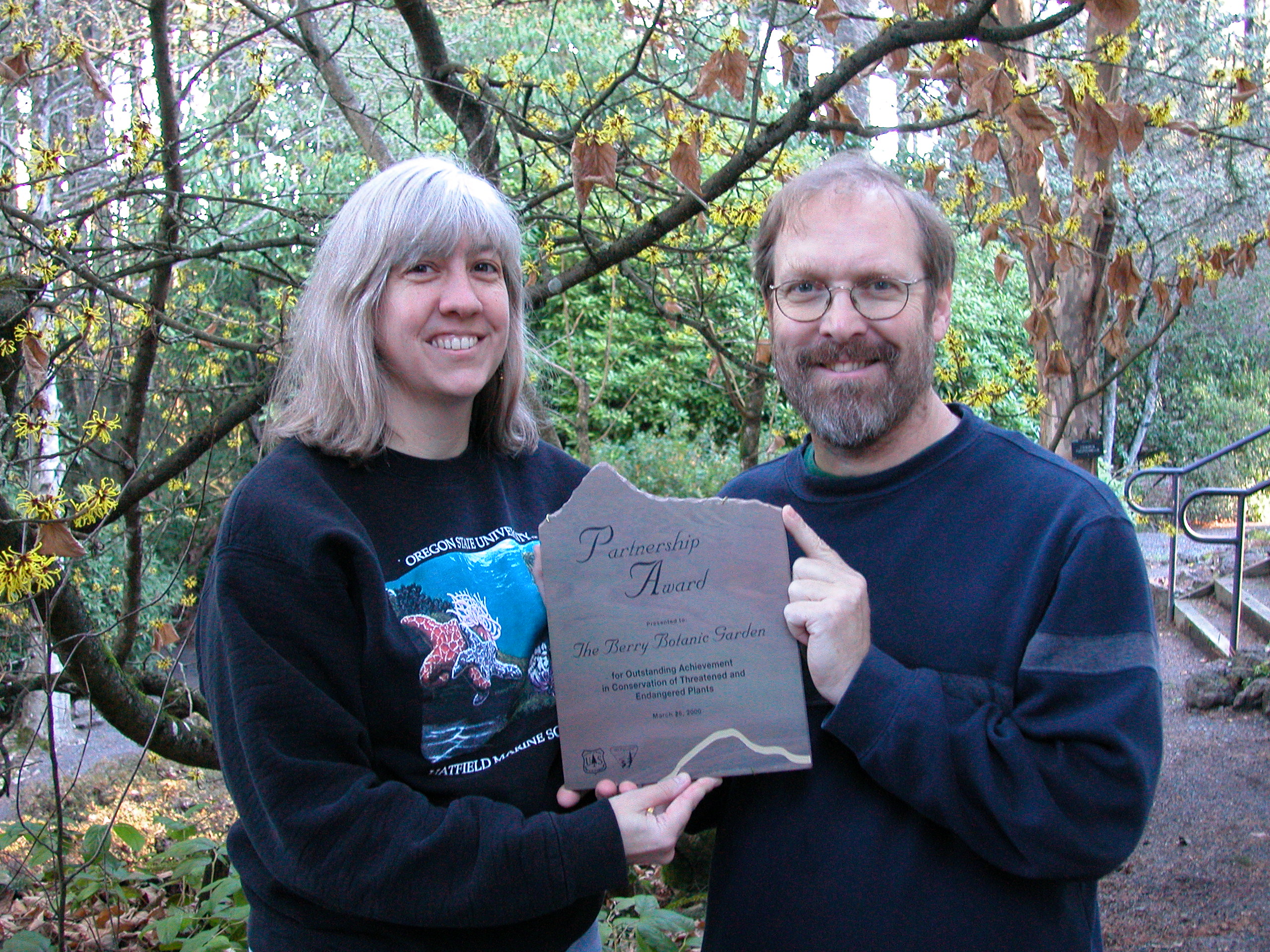

Rather than any one project, I find success in the tremendous growth of the Berry Seed Bank, and in the improvement I have seen in our seed bank practices. The Berry Botanic Garden Seed Bank for Rare and Endangered Plants of the Pacific Northwest which began with an exclusive focus on rare and endangered plants, has expanded to include more common plants as well.

What accomplishment are you most proud of achieving in your career?

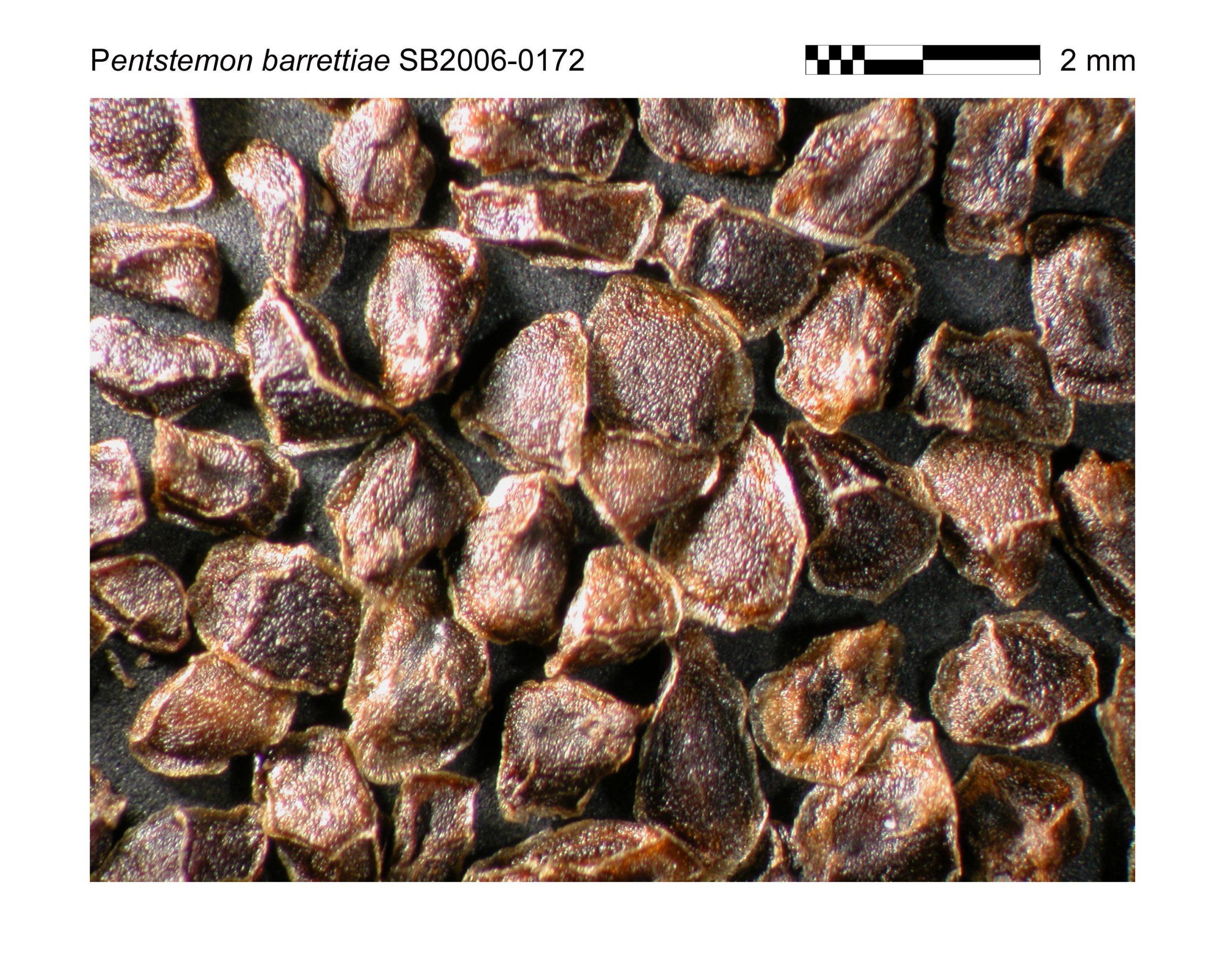

I would like to think my work was important in establishing the practice of collecting and maintaining seed samples by maternal line, as opposed to bulk collections (with apologies to so many whose work load was increased by the switch from bulk collections. I feel your pain.)

How has the world of plant conservation changed throughout your career?

Perhaps the biggest change was the increased scientific and technical rigor, due in no small part to the CPC itself. When I began this work, the Berry Botanic Garden was a tiny, out of the way estate garden that had a seed bank. Although trained in botany, ecology and evolution, I didn’t really know anything in particular about collecting and banking seeds, or the role ex situ methods played in the larger plant conservation picture.

I found in the CPC annual meetings a fabulous group of conservation practitioners and scientists, who formed the essential core of my professional community.

Through its experience and the books that experience has informed, the CPC is a world leader in the development of ex situ plant conservation of rare plants. I have been privileged to have my career begin early in this process, and thus be able to play a part to help conserve rare plants in the USA and around the world.

In what area of plant conservation do you see the need for research and hope someone picks up?

The specter of global climate change has begun to emerge as perhaps the most significant threat to biodiversity with which the world’s ecosystems have had to contend, certainly during the lifetime of the human species.

I think the CPC is well positioned to serve as a catalyst to help develop an expanded vision and methods to include currently common species. Assuming climate change will cause serious ecological disruption over the coming decades and centuries, what sort of collections will our descendants one, two hundred years from now value the most?

What are you looking forward to most in retirement?

First, I’m looking forward to less stress and to having more time for other pursuits than working as much as I have. Ultimately, I want to travel more and get back to drawing and watercolor painting. I’d like to combine travel, art and whatever professional plant conservation skills I have, and put them to use in different places.