Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

March 2019 Newsletter

A few years back, I was reflecting on mentors in my life and had somewhat of a revelation – the majority of them have been women. Some early influences included my mother, an avid gardener, and my aunt, a grade school teacher and advocate for science. Later on, women mentors including teachers and volunteers at zoos and gardens helped shape my thinking. Today, many of my colleagues are women, many of whom continue to challenge me and help me to grow.

For those of us who work in plants and conservation, my story is not unique. This is a heavily women- dominated field after all. Within CPC and our extended network for example, the majority of our Conservation Officers are women. And the entire CPC National Office is made up of women (excluding me, of course). While the reasons for this are varied, one thing is certain – we Save Plants because many smart women are working hard to make it happen.

In celebration of International Women’s Day this month, our March issue of SavePlants highlights a few of the careers of notable women among us working every day in the name of plants. From in-the-field conservationists to lab-based conservation geneticists, and every conservation job in between, women are making our mission possible. Read on and be inspired like I have been by these remarkable conservation practitioners.

I should say that pulling together this issue of SavePlants has been challenging, mostly because there are so many notable women among us deserving recognition. For every one mentioned here there are many others who work every day to ensure a greener future for all. Thanks indeed to Ann-Cathrin, Christa, Joyce, Katie, and Maureen at CPC, as well as all the other remarkable women who represent our network. We greatly appreciate all that you do to Save Plants.

A Career Grown by the Needs of Rare Plants

Joyce Maschinski didn’t imagine herself as a rare plant botanist, let alone Vice President of Conservation and Science at the CPC. The beautiful Arizona leatherflower was the first rare plant to catch her attention and turn her career – the first of many plants and colleagues to steer her towards her current role.

Despite completing a doctorate in botany, I, like many people, didn’t realize there were endangered plants in the U.S., much less in my neighborhood. I was aiming for an academic career when U.S. Forest Service botanist Renee Galeano-Popp hired me to evaluate the impact of timber harvest on Arizona leatherflower (Clematis hirsutissima var. hirsutissima), a rare perennial in the buttercup family. Using my scientific skills as a plant ecologist, I discovered that I could actually help protect this rare plant species. It was a realization that changed my career direction and ultimately led to the varied, interesting, and successful conservation of many rare plants across the nation. Solving the puzzles of rare plant population decline often required tools or methods outside of my experience, motivating me to seek collaborations with scientists or members of the public. These collaborations benefited the rare plants, and in turn, steered my career in new directions.

An example of that was my first population modeling, and my first rare plant reintroduction adventure conducted in the early 1990s. Sue Rutman, botanist for U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service had been monitoring sentry milkvetch (Astragalus cremnophylax var. cremnophylax) at Grand Canyon National Park for several years, documenting its decline. This tiny mat plant grew on Kaibab limestone platforms at a very popular overlook and suffered from trampling. Using Sue’s data, and collecting more after the population was fenced, I enlisted a colleague, Robert Frye, to help us model the population differences between the two. While it may seem common sense that the population would benefit from fencing and diversion of human traffic, proving it with data is more powerful. Showing positive growth projections into the future sure enhanced the protection for that little plant!

Documenting is one thing, actually helping improve the sentry milkvetch population numbers was another. For the reintroduction, I dutifully collected only 10% of the fruits produced one season and sowed 226 of them at the canyon in a replicated microsite experiment. Only two of them germinated. Reporting my results as a failure at one of my first CPC meetings only to have my CPC colleagues assure me that such low field germination is not uncommon and not a failure was another major “Aha!” moment in my career. Now I realize that it is important to begin a reintroduction with thousands of seeds! And ever since that time I have counted on the wise advice of my CPC colleagues to help me solve rare plant problems. By the way, one of those seedlings grew up to be a big momma, surviving and producing many offspring! Other seeds sprouted from the efforts. Plant conservation heroes at The Arboretum at Flagstaff and Grand Canyon National Park expanded the population and restored major portions of its habitat.

My plant conservation experiences, along with the wisdom of colleagues in the CPC network, culminated in the recommendations provided in the CPC Best Plant Conservation Practices Supporting Species Survival in the Wild. I have seen that my efforts from seed collection through cultivation and reintroduction have reduced extinction risk of many plant species. It’s been a great and fulfilling journey.

From Field to Garden

Honolulu Botanical Garden’s new horticulturist and curator comes from a field background – trekking to remote areas to monitor and protect the rarest of the rare plants in Hawai’i. Now that she’s found her way into horticulture, Talia Portner hopes to bring what she learned while immersed in wild habitats – and a few of those rare plants – into the garden with her.

Talia Portner, Honolulu Botanical Garden’s (HBG) curator and horticulturist, comes to the horticultural world through her years of working with rare plants in their natural habitats. This background has taught her about the needs of plants and instilled in her a natural aesthetic. Talia hopes to incorporate both of these traits, with all she is learning from her colleagues, into the five gardens she works with across O’ahu.

Though her biology education focused on human biology, Talia was quickly drawn into the world of plants and the plight of rare plants as she entered the workforce. There is no shortage of rare plants in Hawai’i, with so many naturally rare endemics and so many threats wrought by changes to the islands. Talia spent nearly thirteen years with Hawai’i’s Plant Extinction Prevention Program (PEPP), working with the rarest of the rare in Hawai’i – the species with less than 50 wild individuals remaining. In the field working with these species, and enjoying seeing them in their natural habitat, Talia repeatedly encountered the hardships of working with such species in the wild. The long treks out to field sites which only allowed for limited work to get done, the small populations, etc. helped her recognize the need for conservationists to be able to access these plants in a different setting.

-

Euphorbia haeleeleana, the Kauaʻi spurge, is a species of flowering plant in the croton family, Euphorbiaceae, that is endemic to the islands of Kauaʻi and Oʻahu in Hawaii. Like other Hawaiian spurges it is known as `akoko. (from Wikipedia). -

Koko Crater Botanical Garden’s recently retired manager, Robin Sunio, checks on Kaua’i spurge. -

Koko Crater Botanical Garden’s recently retired manager, Robin Sunio, checks on Kaua’i spurge.

Partners within PEPP, including CPC institutions Harold L. Lyon’s Arboretum and HBG, have taken in these rare species, and Talia hopes to use her new position at HBG to expand their role in inter situ conservation. Always having been able to see the big picture in situations, Talia is excited to become a bridge between the in situ conservation work of her experience and the important ex situ collections she can influence now as she serves as a curator acquiring plants for the gardens.

Koko Crater Botanical Garden, for instance, presents a great opportunity for inter situ conservation. The 60-acre garden on the basin floor of a dormant volcano supports 50-year old native plants that the public rarely gets to see and has had been part of some great conservation projects. Learning from the garden’s recently retired manager, Robin Sunio, she learned how to incorporate knowledge of the climate and trends into decision making at the garden. As someone who spent a lot of time making observations in the field, Robin’s observation approach to garden management proved invaluable during her transition into the garden. Talia sees Koko Crater, and its amazingly fertile soils, as an ideal garden to increase the number of wild-collected individuals, by collaborating with partners in the field as well as the Lyon Arboretum seed lab.

Talia brings with her many of her connections from PEPP, many of whom are, like herself, excited to see HBG grow their conservation work. At a recent meeting with the state botanist on O’ahu, her former PEPP supervisor, the two quickly identified a list of a dozen species for future collaborations. One of the species, ha’ele’ele’ana or Kaua’i spurge (Euphorbia haeleeleana), is a dioecious species (having separate male and female plants) whose five individuals in the garden have yet to produce fruit, limiting their conservation value. Talia hopes to bring in more males to increase the amount of pollen.

Gardens such as HBG are great receptacles for plants too difficult to meaningfully work with in the field. And they are also a great venue for outreach and education. Learning more about garden design, building on her experience in the floral design business and her natural aesthetic strengthened by her time in natural habitats, Talia looks forward to building more ‘habitats’ into the gardens. Display is an opportunity to educate, and displaying trees with their associated species from the wild presents a great opportunity to help educate the public on the amazing flora of Hawai’i.

Though Talia’s career has spanned different disciplines, each has been important in rare plant work. She is bringing what she learned in one arena into the next, and reminding us that the lines between disciplines are not hard and fast. Plants benefit when conservationists don’t do their research and work in isolation, but keep the connections between their work strong.

Some years ago, CPC held a board meeting in Cincinnati, and one of the field trips was somewhat unusual – to visit the grave of one Emma Lucy Braun. This eminent scientist, and plant conservationist, has inspired many in the CPC network and decidedly deserved the homage paid to her.

From vouchering species across the landscape to laboratory work studying the relationship between plants and bacteria and everything in between, botanical studies in the US have been supported by women throughout history – even in times when women weren’t always prevalent in science. Emma Lucy Braun (Lucy), Ph.D., is particularly notable not only for the work she did, but the recognition that she received in an era when, despite great work and potential, such recognition wasn’t always given. In this issue, Valerie Pence, Ph.D., recognizes Lucy Braun as an inspiration in her plant conservation efforts, and it can be safely assumed that Valerie isn’t the only one.

Lucy Braun was an early advocate of plants. She established the Cincinnati chapter of the Wild Flower Preservation Society in the 1920s and also served as editor of the organization’s journal. She worked to conserve the 22 acres of Lynx Prairie that eventually led to the establishment Edge of Appalachia Preserve System and home to several rare plants.

Upon cataloguing an updated flora of the Cincinnati area in the 1930s, Lucy Braun compared it with the flora completed 100 years prior, providing a model for analyzing changes in a flora over time. Her book Deciduous Forests of Eastern North America, originally published in 1950 is still readily available. She described multiple species, and has had multiple species named in her honor. She served as the first female president of the Ecological Society of America and received many awards and honors for her work as a botanist and ecologist. And, not only did she accomplish great things herself, but she helped introduce other women into the world of botanical research, with nine of her fourteen graduate students being women. She did so during a time when it was uncommon for female professors to mentor any graduate students.

Lucy Braun’s work with and for plants stands today and is truly inspiring to all of us who strive to save plants today.

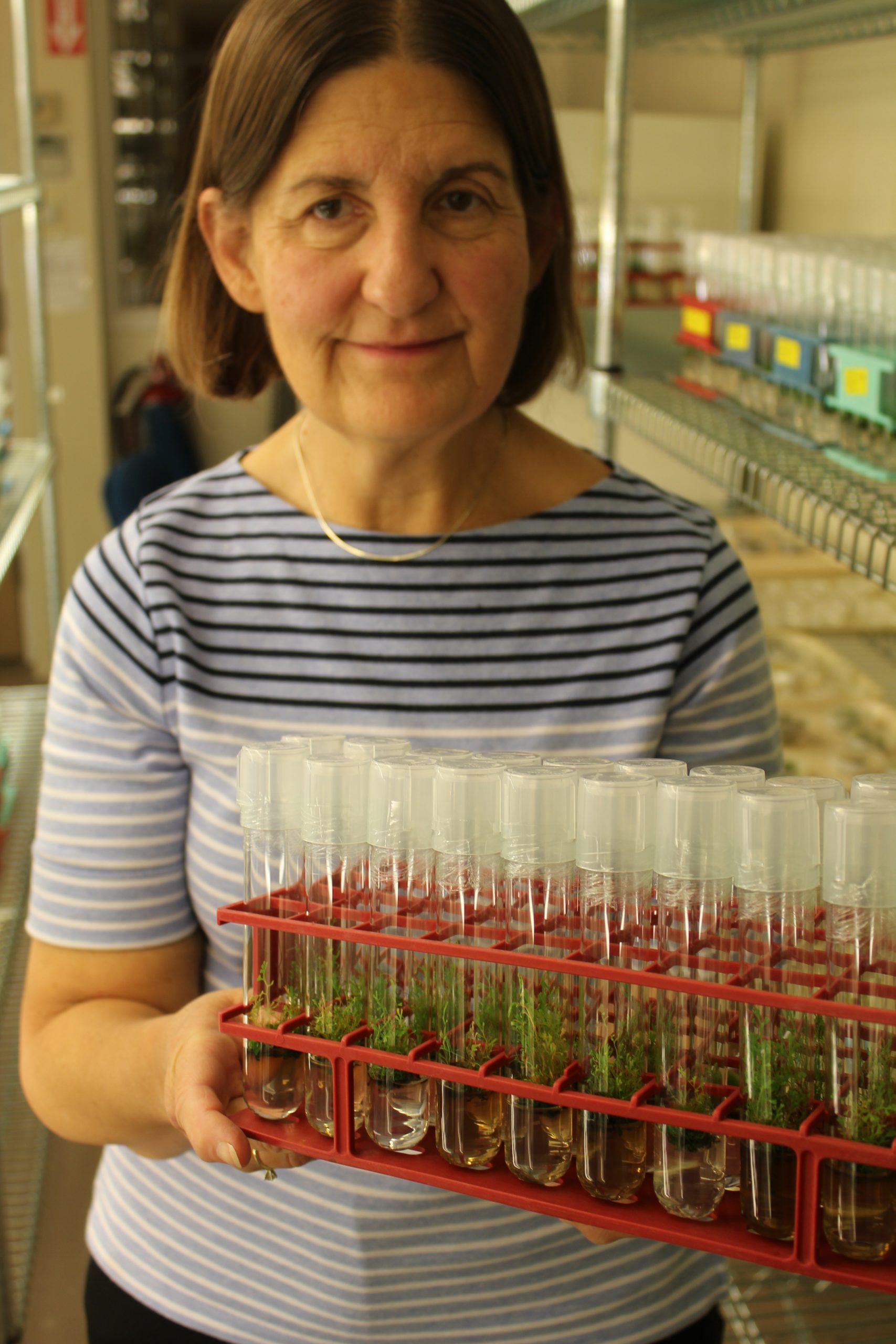

Valerie Pence, Ph.D.,

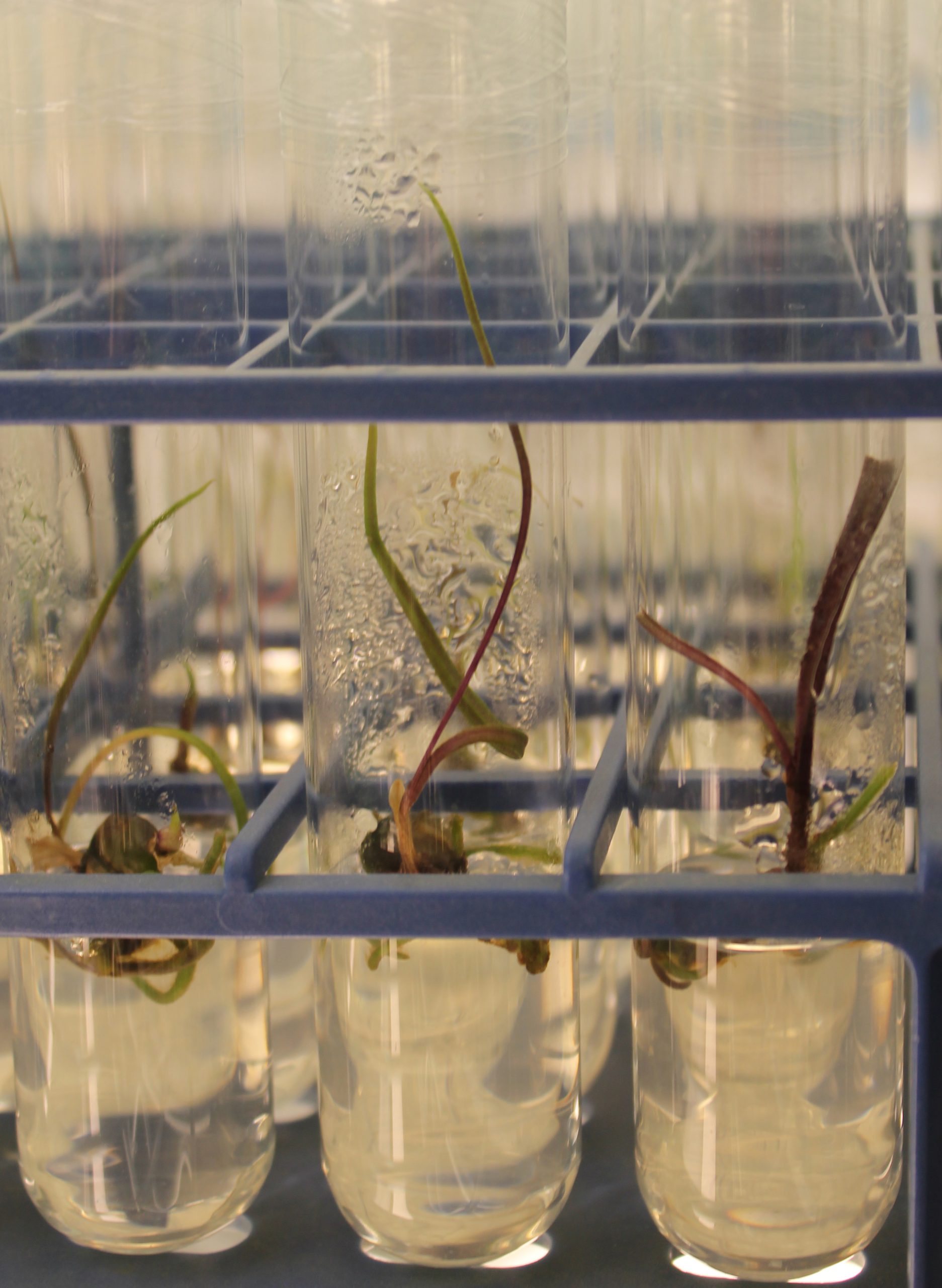

Brought into conservation through her interest in tissue culture, cryopreservation, and plant developmental systems, Dr. Valerie Pence and her Exceptional Plant program at Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Garden’s Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife have been vital to saving rare plants unsuited to seed banking. Many CPC participating institutions – and their National Collection species – have benefited from Valerie’s work, as collaborators and in building on her pioneering work.

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I first became interested in plants in college. I grew up in a very urban neighborhood and disliked my high school biology class. While retaking biology my first semester in college, I wound up fascinated and wanted to learn more. Not ready to dissect animals in my second semester, I opted for botany, with the fear that it would be boring and there might be only a couple other people in the class. It was team taught by two young and enthusiastic professors, with about 50 people in the class. After that I was hooked.

What was your career path leading up to your position as Director of Plant Research at CREW?

For my Ph.D. I worked on an aspect of the crown gall disease and Agrobacterium tumefaciens, for which I had learned tissue culture methods. I realized in the end that I was more interested in the tissue culture and plant developmental systems than in crown gall itself. I was then fortunate to have two post-doc positions after grad school both dealing with in vitro systems.

Later, as a Research Associate at the University of Cincinnati working on responses of a tomato mutant in vitro, one of the herbarium professors, Vic Soukup, would walk by the lab and see me working on tissue culture. He would stop to talk and ask questions, and one day he asked if I would be interested in trying to put Trillium, a genus he as an expert on, into tissue culture. I thought that sounded interesting, and agreed to collaborate. We eventually published 3 papers on Trillium species in culture, including the rare, Trillium persistens.

Vic was a member of the Cincinnati Wild Flower Preservation Society. He asked if I would be willing to give a talk to the group on the work with Trillium. Just about that time, the Cincinnati Zoo decided that it was going to recognize its longstanding commitment to its gardens, as well as its animals, by changing its name to the Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden. In conjunction with this recognition Betsy Dresser, founder of what has become the Center for Conservation and Research of Endangered Wildlife (CREW), wanted to add a plant research component to CREW. With CREW focused on cryopreservation and in vitro for animals, Betsy asked the Director of Horticulture, Dave Ehrlinger if he knew anyone who might be able to develop a similar program for plants. Dave, also a member of the Wild Flower Society, had attended my talk on Trillium. He suggested me to Betsy and I’ve been here ever since.

What about working with plants has surprised you?

Given my lack of interest in them up until college, I would say that at that point I was surprised at how interesting they are. I think now I’m fascinated by the incredible diversity of plants, and in their adaptations to so many different environments.

What drew you to work with exceptional species?

In a way, the work with exceptional plants developed in reverse. Because of my interest and training in in vitro systems and the emphasis at CREW on cryopreservation, those were the methods we focused on in the Plant Lab.

It naturally evolved that we were working with those species for which there were particular difficulties with using traditional methods for propagation or preservation—plants that were producing few or no seeds, or plants with little seed production because there were few plants, or plants with recalcitrant seeds. We were fortunate to have several grants from IMLS for developing protocols for species nominated by the CPC network, and that helped develop that area of work.

Please share one of your plant conservation projects.

The autumn buttercup restoration project has been so rewarding to be a part of because of the partners: The Arboretum at Flagstaff (TAF), The Nature Conservancy, U.S. Fish & Wildlife, and Weber State University. We’ve produced hundreds of plants through tissue culture that were acclimatized by TAF, and later outplanted on a TNC preserve in Utah. It’s been a great group to work with and a fascinating project. I’m also very excited about a project funded by our current IMLS grant, which provides seed money for in vitro or cryo research on exceptional plants in 11 other institutions, most of them CPC gardens.

What has been the most challenging aspect of your work?

Plants. The variety of plants and their responses in vitro and to cryo is challenging, it but is also the most interesting part of my work. I would like to understand more about how those responses relate to the natural adaptations of the plant. If we knew more about that, we might be able to better predict what methods would be the best for each species. A secondary challenge is educating people on the fact that plants are important and are species in their own right, as much as animals are.

Please discuss any women in science who have inspired you through your career.

I attended a women’s college, Mount Holyoke College, and the majority of professors in biology and chemistry were female. The model that women could succeed in science was accepted as normal. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve had the opportunity to meet and collaborate with some younger women scientists and have benefited from their energy and enthusiasm. And, of course, there is Dr. Emma Lucy Braun, who, in this part of the country, is an iconic figure in plant ecology, botany, and conservation, as well as a pioneer woman scientist of the early to mid-twentieth century. I first learned of her in my first year at CREW, when I met some long-time Cincinnati nature lovers. They commented that Lucy Braun would be very happy about what I was doing with plants, and I had to go look up who she was. I would never put myself in her league, but I think those of us in plant conservation are certainly trying to follow in her footsteps.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today