Save Plants

CENTER FOR PLANT CONSERVATION

June 2020 Newsletter

Since mid-March 2020, many of us have been secluded in an effort to suppress the COVID-19 contagion. Over the months of the pandemic, we have seen that communities of color have suffered disproportionately high impacts of mortality and unemployment. Recent anguishing brutality further ripped the veil, leaving us speechless with sorrow.

The CPC National Office wishes to express our heartfelt condolences to the families of George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and many others from communities of color, who have suffered violence and injustice for far too long. We stand in solidarity with our neighbors to denounce brutality and call for a unified compassionate acknowledgement that racial justice is vital to social, economic, and environmental well-being.

In such painful times it is difficult to remember that plants are part of a path to a better way, a better self, better health, better community. Interactions with plants help us coalesce our inner self with outer beauty, peace, and nurturing. The CPC mission statement, approved by our Board of Trustees in May 2020, “Safeguard and conserve imperiled native plants by advancing science-based practices, connecting and empowering plant conservationists, and inspiring people to protect biodiversity for future generations,” elaborates what, how, and why we Save Plants.

Protecting biodiversity for future generations is a tall order and one that is absolutely impossible without civility and social justice for all people, regardless of skin color. As an American who grew up pledging liberty and justice for all, I must admit that, clearly, we as a nation have a long way to go to realize that ideal. I also must face a call to action to ensure that the Center for Plant Conservation, as a conservation organization, and I, personally, are rays of hope, rather than contributors to the problem.

Perhaps it is time for reconciliation as a path to healing – recognized respect, trust and unity. In the field of ecology, this term is used to suggest that humans may share the spaces they use with wild species in such a way that both thrive. Our CPC gardens are places of ecological reconciliation, places of harmony and mutual respect between wild rare plants and humans.

In the midst of the pandemic and social unrest, how did we continue to do plant conservation? Truly, COVID-19 posed many challenges for our work to safeguard and conserve imperiled native plants. In some areas of the nation, we haven’t been able to leave our homes and we haven’t been able to enter the areas where our rare plants live, while in other areas of the country we have found ways to continue our conservation work. The secret has been continued connections, patiently accepting delays, and adjusting – sometimes switching to tasks that can be accomplished indoors. The secret is always persistent optimism. With careful adherence to social distancing and maintaining clean spaces, our important plant conservation work has continued.

As our Conservation Champion Jennifer Ceska reminds us, we of the “Plant Tribe” know that plant conservation requires long-term commitments. We commit to our conservation work while ensuring kindness for ourselves, our loved ones, our colleagues, and our community. We do this so that our children and great grandchildren may inherit a healthy and sane planet.

Wishing you and yours safety and health,

Joyce Maschinski

CPC President & CEOField Conservation in the Time of COVID-19

Working from home is all well and good for many conservation tasks. But rare plants are found in their habitats – decidedly outside of home offices. Plants’ homes must be visited to monitor populations, collect seed, conduct management activities, and more. Field work is usually at its peak in the spring and summer, with many plants in bloom. But COVID-19 has changed the logistics of this work for many CPC institutions – some more than others.

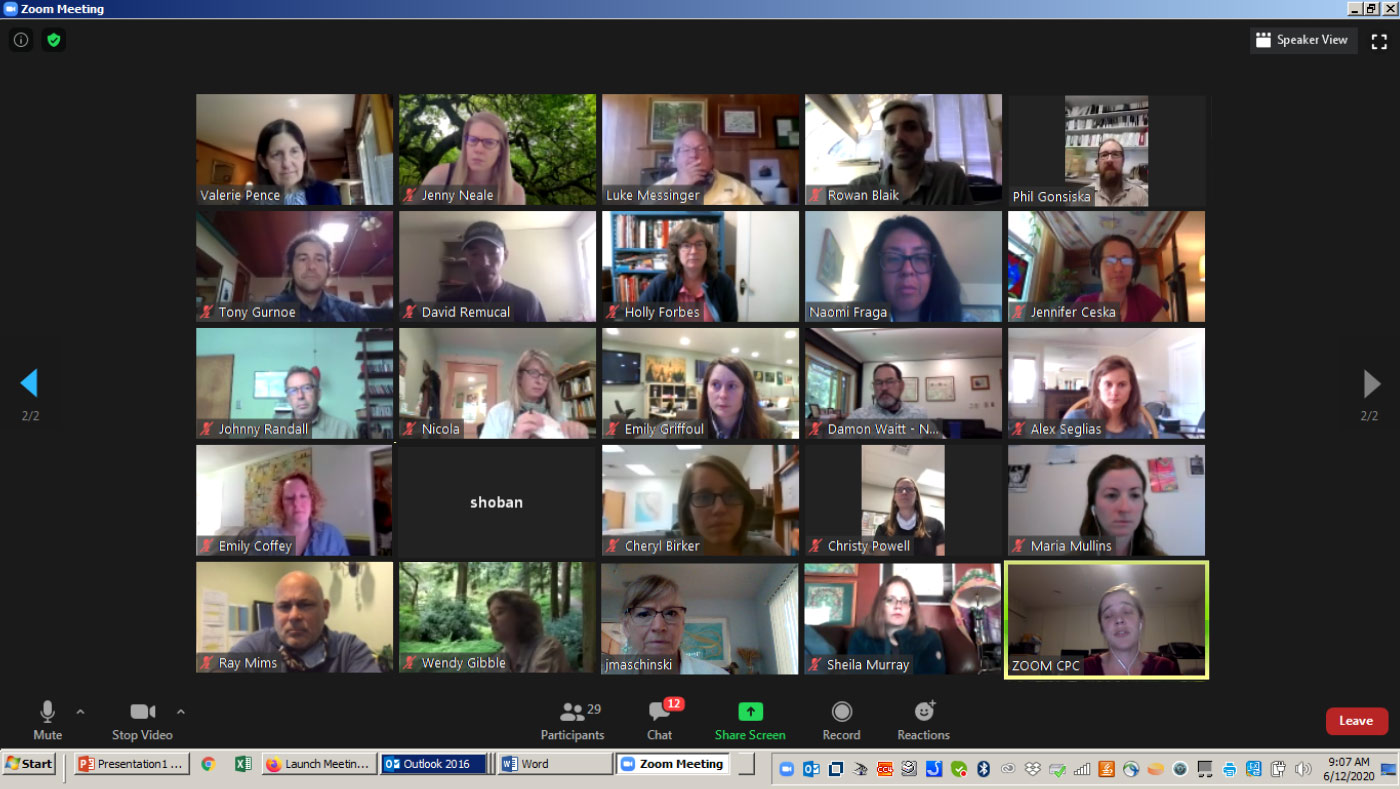

In May, CPC hosted the first in a series of online meetings giving conservationists from our Participating Institutions the chance to share some of their experiences and challenges with continuing or restarting field conservation work across the country. It became clear that there are vast differences between regions (even within the same state), as well as institutional differences in policy and approaches.

Conducting field work does not preclude the need to follow social distancing regulations. While it seems straightforward to keep a minimum of six feet of distance and/or wear a mask when in the field, these requirements do present challenges. Tom Kaye, Ph.D., executive director of the Institute for Applied Ecology (IAE), requires his team members to stay six feet apart in the field. He has noted complications arising in training and answering specific questions in the field, but they are getting the work done. This year, the IAE teams have already worked on projects monitoring reintroduced populations of the threatened golden paintbrush (Castilleja levisecta) – using separate equipment where possible, sanitizing shared equipment between uses, wearing masks, and staying physically distant.

Transportation is a recurring issue with field work, and adjustments for COVID-19 are leading to lost efficiency and added expense. Because a vehicle has many surfaces and a small airspace, current recommendations are that team members not share vehicles for long durations. But field vehicles are in short supply for many institutions, and the unplanned use of multiple vehicles affects project budgets. The IAE team is facing these issues. To monitor Cook’s desert parsley (Lomatium cookii), which requires overnight travel, Kaye’s team drove separately, camped and cooked separately, and worked in the field separately. Although this method was slower and a bit more expensive, they were able to get strong data on existing populations and seedling recruitment in reintroduced patches. Other institutions have not fared as well with budget changes, however, and are seeing greater impacts on field work. Even where field work continues, the budget impacts add up.

The University of California Botanical Garden (UCBG) has had a very different experience during this field season and is just starting to get back into field work. The university took a strong stance against field work until recently. In late May, curator Holly Forbes was excited to receive permission to conduct field work, but it was still limited to staff only (no volunteers) with a maximum of two staff per vehicle. As solo field work is uncommon due to safety concerns, this limitation does not actually open up field opportunities very much. The mandate to work in teams is further complicated by indirect COVID-19 factors. Due to cutbacks in staffing at the garden, increased plant care duties leave less time for the team to conduct field projects, and some staff also need to juggle childcare duties.

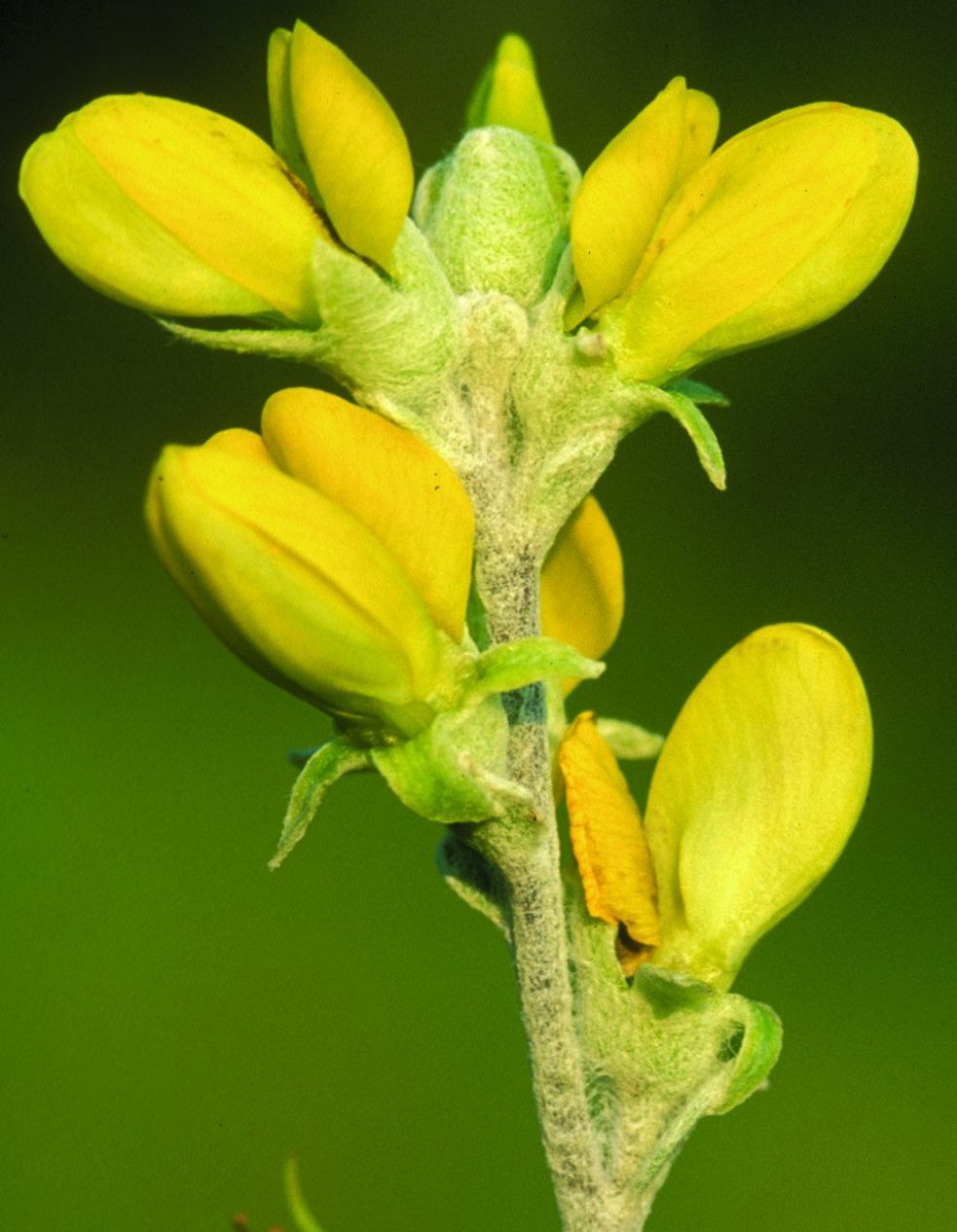

Still, the loosening of restrictions by the university is now allowing the team to tackle some of their conservation priorities. The endangered Baker’s larkspur (Delphinium bakeri) is in need of monitoring to better inform reintroduction strategies. This project, thought to be lost just a month ago, is now a possibility. Unfortunately, the field season for several early-flowering taxa has passed. The UCBG team is now focusing on taxa with phenology (cyclic and seasonal traits, including bloom and fruiting times) that match opportunities in their schedule.

The closure of lands with rare plant habitats, and of campgrounds and other facilities, has also impacted field work. The UCBG team missed the season for one taxon on Bay Area park land. The IAE team has had to delay projects requiring overnight stays in motels or campgrounds, which are closed in Oregon. For both institutions, this means projects are pushed back a full year.

These are just two of the experiences of institutions that participated in the CPC meeting. Our Participating Institutions across the nation are all adjusting to field work during the pandemic. Some reported minimal impacts (North Carolina Botanical Garden). Others reported working out guidelines for their staff (Desert Botanical Garden), limiting work with staff at partner institutions to reduce contamination (National Tropic Botanic Garden), and other adjustments. Field work guidelines and protocols will continue to evolve. But the take-home message of the meeting was clear: saving plants is the top priority for all of our Participating Institutions, and they are committed to identifying and implementing the changes needed to safely achieve this goal in the time of COVID-19.

Photo credit: Vanessa Handley, Ph.D., courtesy of University of California Botanical Garden.

Forging on Despite Lonely Labs

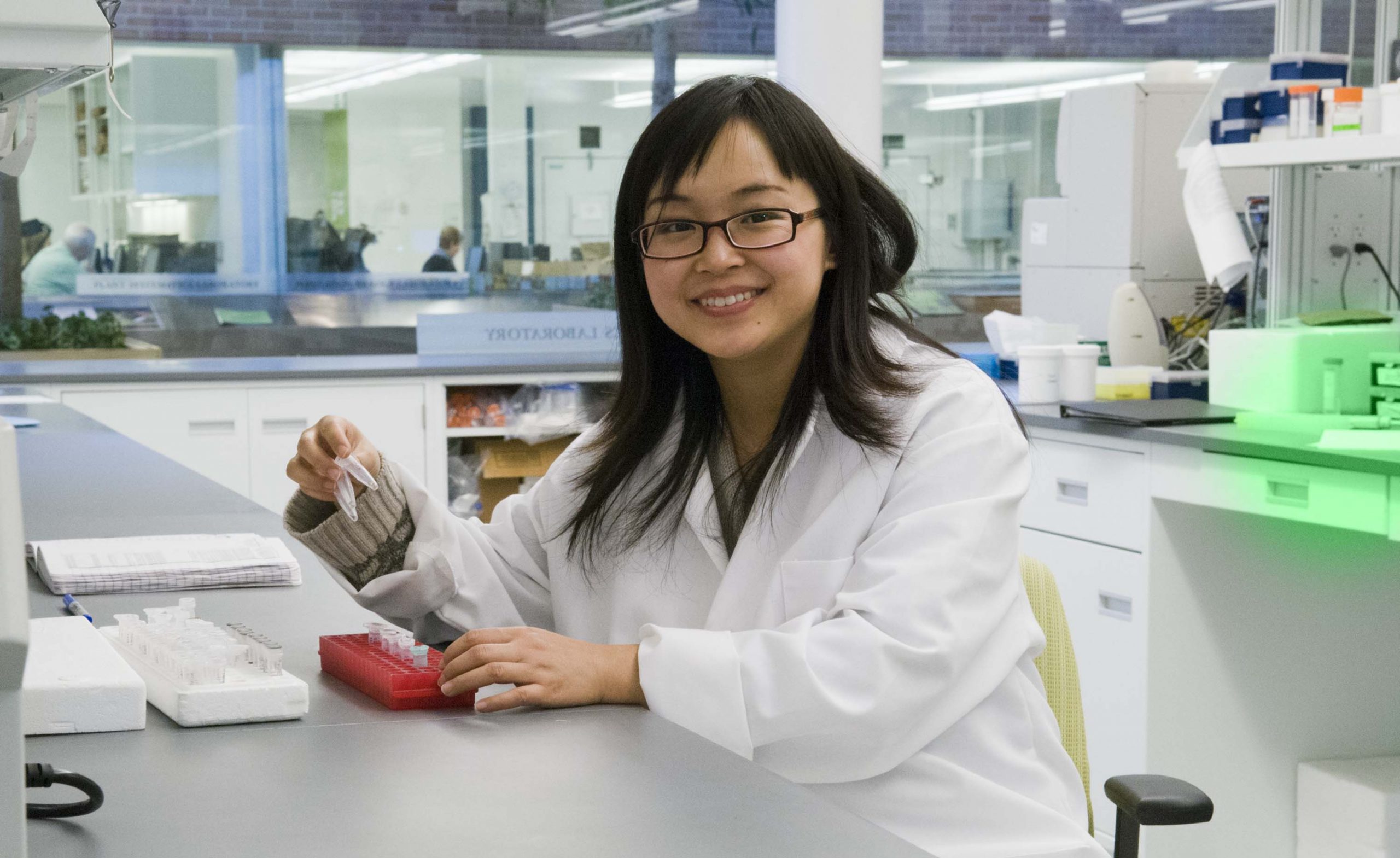

As I entered the Beckman Center of the San Diego Zoo’s Institute for Conservation Research (ICR) for a quick gear pickup, the empty eeriness of the building was striking. The building contains many lab spaces that are designed to be shared and often bustle with activity. But the labs have largely been idle since March, when California instituted its COVID-19 stay-at-home orders.

Most of the ICR’s labs are now fully shut down, with exceptions for those involved in animal care. The shutdown took effect quickly and a bit unexpectedly, following a possible COVID-19 case amongst staff. The safety team put strict sanitary measures into place and limited building access while projects were being shut down. Looking forward, as orders are lifted but health concerns remain, we also face changes in how the labs will be used in the future.

Other labs around the nation have had similar experiences. Our colleagues at Chicago Botanic Garden (CBG) spent the days before their shutdown orders moving plants from growth chambers to greenhouses, shutting down tissue culture work, prepping the seed bank for closure, and more. A small number of horticulture, natural areas, and grounds staff remain on site to keep collections alive. Security staff have also now been allowed back in the garden.

In contrast, sporadic access to ICR facilities has been allowed in San Diego. Visits are carefully scheduled – and heavy on PPE (personal protective equipment) and sanitation – to allow very limited tissue culture work to proceed, albeit at a slower pace. Post-doctoral fellow Joseph Ree is continuing his care of endangered Nuttall’s scrub oak (Quercus dumosa) plants (deemed essential) as well as experiments in controlled aseptic conditions. The tissue culture area, located in a separate facility from most of the other ICR labs, is an isolated room now limited to one person at a time. Cleaning all surfaces after each visit drastically reduces the chances of viral transmission. In fact, the lab space, by nature of its purpose, was already a “clean” room.

Although many labs in CPC’s Participating Institutions are currently idle, the researchers are certainly not. At the Chicago Botanic Garden, staff pivoted to a new focus when their molecular genetic work was put on hold. CBG’s IMLS-funded pedigree management project (featured in the November 2018 Newsletter) forged ahead, with a focus on database and software development, as well as creating a project website, conducting literature reviews on target taxa, and any other aspect of the project that could be tackled from home.

Other projects within CBG’s conservation programs have dived deep into tech development. New websites and mobile apps for community science projects, Budburst and Plants of Concern, have been tackled in home offices. And, of course, writing grant proposals and papers are taking a front seat. Another silver lining is that the reduction of lab work provides more time to research the literature and better design upcoming high-impact experiments.

At ICR, the seed bank team has taken to turning home offices into small seed-processing labs. Working with one accession at a time, and with care to keep seed cool and dry, the team has been processing seed lots in sieves and by hand at home. With sporadic visits to the regular seed processing lab (also a separate facility), processed seed is quickly returned and a new accession is taken home. The work is slow, and the help of volunteers is missed, but the conservation work continues.

Even as stay-at-home orders are being lifted, restraints on lab time will persist. Social distancing and hygiene adjustments will alter how people work. In Chicago, Kayri Havens, Ph.D., and her team are preparing for a partial reopening this month. They have determined the maximum number of people for each lab and are scheduling access accordingly. Priority access is given to graduate students, who need to finish projects to graduate, and post-docs who also have time restraints. Only a couple of staff will be on site, largely to oversee the labs and ensure that safety procedures (i.e. masks, social distancing, and cleaning surfaces) are followed. For the busier labs at ICR, a similar approach is being planned. Time in the genetics lab will be in particularly high demand for both plant and animal teams.

Happily, the important conservation work of these institutions continues, despite the necessity of a slower pace. Changed timelines will clearly need to be addressed. Chicago Botanic Garden is already requesting no-cost extensions for several grant-funded projects.

Many CPC institutions, finding their conservation programs similarly constrained, are facing significant impacts on project timelines and budgets. But for none of them has the waiting time become time lost. Researchers are digging deeper into the literature, formulating new projects and experiments, and getting creative in their stay-at-home tasks. Our collective passion for plants is undaunted. Our work to conserve them continues.

As Seen on CPC’s Rare Plant Academy

In May’s CPC online meeting of member conservationists, staff from the National Tropic Botanic Garden discussed shifting focus in response to the impacts of COVID-19 on field and lab work. Preparation of documents for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species is one worthy task that has often been precluded by limited staff time.

During CPC’s 2019 National Meeting, Anne Frances of NatureServe expounded on how NatureServe (and, similarly, Red List Assessments) use field expertise of conservationists who work with species on the ground to establish their rankings. Many experienced field workers have the information needed in their datasheets or in their heads, and the limitations on field work make this a great time to put this into a format for official assessment.

Jennifer Ceska, Conservation Coordinator, State Botanical Garden of Georgia

Amidst these times of great human suffering, it is important to remember rays of light that can outshine the darkness. Our Conservation Champion Jennifer Ceska is such a radiant being. She customarily calls colleagues “beloveds.” When she wraps her big smile and warm heart around a crowd, it will follow her anywhere. Her nurturing attention has helped the Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance thrive over many years and even during a pandemic. We wish we could clone her!

When did you first fall in love with plants?

I fell in love with plants when I was a little girl growing up in Grand Prairie, Texas. My Mom always had the most glorious flowers in a large garden bed lined with railroad ties in our front yard; they were the brightest colors in our neighborhood. We didn’t have much money, but we had petunias of every color combination. Our neighborhood was an LBJ-funded new development, quite literally in the middle of open prairie and pastures. Our sidewalks were lined spontaneously with Oenothera speciosa. We called them buttercups. They were my most favorite. There was a single bluebonnet in a field behind our school. My class circled it in alarm, with someone shouting, “Don’t step on it or they’ll put you in jail!” This was the God’s own truth as far as we were concerned. Though there have been detours, I’ve followed wildflowers ever since.

What was your path to becoming a botanist with the Conservation Coordinator at the State Botanical Garden?

I knew I wanted to do something very applied, both in graduate school and in my career. And I knew I wanted to work in a museum, and at best, one tied to a university. I thankfully received the Catherine Beattie Fellowship in 1994, awarded by the CPC and the Garden Club of America, funding my travels to botanical gardens with well-established plant conservation programs. We chose six CPC gardens on the east coast. That experience helped me to draft a strategic plan for developing a plant conservation program for the State Botanical Garden of Georgia, my home garden in graduate school. When I presented my exit seminar to the garden’s board of advisors, the chair, Mimsie Lanier, approached me and my major professor, Jim Affolter, offering to raise funds for a new conservation coordinator position. It took Mimsie two years and me holding tight through a series of temp jobs in offices around town, but she did it!

What about working with plants has surprised you?

I’ve always been surprised by how poor the relationships are between people and plants. The elders in my life were all gardeners, foragers, hunters, and fisherfolk, and they all knew plants. Garden club members have always been encyclopedic about plants. University campus was a haven for a small group of people who fell head over heels for plants. But most of the people in my daily life – my friends, neighbors, Gen Xer cohort, and audiences in the early days of my career – didn’t know plants could be endangered, didn’t know plants were essential to some animal species, and didn’t see plants when they were just walking down the street. I’ve always stopped to poke around at plants and critters, rocks and twigs. I see great change in this now, and the new generations coming up through the university knock me over with their incoming knowledge of plants, gardens, culinary and medicinal skills, and the insects and birds associated with native plants.

What is your role within the Georgia Plant Conservation Alliance (GPCA), and what do you see as GPCA’s role in conservation?

I serve as the program coordinator for projects and partners in the GPCA, mostly cajoling extremely dedicated conservation biologists of all disciplines to work together on species recovery actions for Georgia’s imperiled plant populations. Truly, they are all rockstars of plant conservation and habitat restoration. I get to celebrate their work, foster relationships between organizations, keep my eyes and heart open to possible connections and collaborations. This team of folks in the GPCA have worked to develop an inclusive and safe space for partnership and a commitment to collaboration that enables organizations to leverage small resources into great accomplishments. People in plant conservation work have to deal with ever-increasing pressures and setbacks on the species we are working to recover, and this can overwhelm the spirit. We lift each other up, and we work hard to celebrate the small victories like first seeds in collection, first germination of a rare species ex situ, or the first year a reintroduced plant flowered in situ.

How did you pull together the GPCA Annual Symposium in the midst of COVID-19?

We had already invited speakers for our usual May meeting, before all university gatherings had to be cancelled because of COVID-19. Our colleague presenters were willing to present virtually, even though that can be challenging. We talked with campus experts and prepared the speakers with ways to engage the audience including polls, videos, and facilitated discussions. We had tips for best viewing and encouraged everyone to take care of their brains during the four-hour meeting. The speakers were all fantastic, from PhD researchers to undergraduate students, from Atlanta Botanical Garden specialists to Georgia DOT game-changing partners. Everyone in GPCA was invited to submit and quickly narrate their own images for “Postcards from the Field.” We love hearing everyone’s field stories for Postcards at our regular meetings, but this meeting welcomed images of home offices and cats and gardens and sweethearts and backyard birds and frogs, enabling us to glimpse our friends’ lives and see that they are fine. With more than 65 people, we had more participation in the virtual meeting than we have had for in-person meetings. And many partners have since replied that they were grateful it was online, because federal travel budgets or teaching obligations often prevent them from attending. We may add a virtual element to all future GPCA meetings.

Why do you think it was important to still do the symposium/bring people together?

One of the most powerful things about the GPCA is our time together, face-to-face, fostering relationships between very diverse organizations, building trust, sharing resources and expertise, sharing techniques and tools, and just spending time with our plant tribe, folks who get our humor and our passion for plants in all their infinite detail. We meet annually every May, and the thought of not meeting face-to-face was disheartening during an already gutted year. Field work plans and goals laid in February fell flat. We decided to try a group Zoom meeting so we could, at least, see each other’s faces. So that was the primary goal for this meeting – to see each other and connect.

What advice/words of hope do you have for garden conservationists in these trying times?

I will share words that have been shared with me, hoping that these are well known to all of my CPC kin. This is a pain-filled and unnerving year, and it is okay to temporarily let go of some responsibilities to which we feel so profoundly committed. We might not be able to collect those endangered seeds this year. We might not get to have a work party for that critically imperiled habitat. We might not have the steam to generate that article or paper. And that is okay. Our goal is to take special care of ourselves and our loved ones and to get through this year together. Plant conservation requires long-term commitments.

In Memoriam

John C. McPheeters

John McPheeters, a long-time supporter and past Board Member of the Center for Plant Conservation died June 8, 2020.

Fifteen years ago, if you walked east from Euclid Avenue in St. Louis and made a stop at the corner of Olive Street and Walton Avenue, you’d be confronted with genuine urban decay and pathological ugliness. Contributing to this squalor were an assortment of vacant and abandoned buildings, an automobile graveyard, a warehouse shuttered with sheets of grimy fiberglass, along with the usual trash and broken bottles, creating an atmosphere of urban rot.

Stand on that corner today, and you can see and touch and feel what a strong sense of civic character and ambitious creativity can produce. The merlin of all this was John C. McPheeters, 73, who died Monday night at home in the West End. The magical place he and his wife and children created is Bowood Farms.

Dr. Art Whislter

The University of Hawaiʻi is saddened at the announcement yesterday of the passing of Dr. Art Whistler due to COVID-19. Art was well-known and beloved by many at UH as well as by the botany and conservation communities across Hawaiʻi and the Pacific.

Art was a botanist who specialized in the tropical plants of Hawaiʻi and Pacific Islands. After earning bachelor’s and master’s degrees in California, he served as a Peace Corps volunteer in Samoa. He then moved to Hawaiʻi and earned his PhD in Botany from UH Mānoa in 1979, with his research focused on the vegetation of Samoa.

Artʻs robust professional career spanned Hawaiʻi and the Pacific. At UH he was a lecturer and adjunct faculty member in Botany as well as at the Lyon Arboretum. He held a postdoc appointment at the National Tropical Botanical Garden on Kauaʻi and was a research affiliate at the Bishop Museum. He spent a year as a visiting professor at the University of the South Pacific in Fiji.

Art founded a small consulting company in Honolulu, Isle Botanica. And as a consultant, he worked on botanical projects across the Pacific Islands including Samoa, Tonga, Niue, Fiji, Tuvalu, Kiribati, the Marshall Islands, Yap, Chuuk, Guam and the Northern Marianas. He was a prolific author of both scientific articles and books focused on plants of Pacific Islands.

He was a scientist, naturalist and educator who touched the lives of students, colleagues and communities throughout the Pacific.

Art is the third reported death in Hawaiʻi from COVID-19 and the first to touch UH so closely. It appears he contracted the virus on a recent trip to the State of Washington and was hospitalized here in Hawaiʻi after his return. Art will be sorely missed.

Get Updates

Get the latest news and conservation highlights from the CPC network by signing up for our newsletters.

Sign Up Today!Legislation to Protect our National Parks and Public Lands Will Save Plants

On Monday, June 8, 2020, U.S. Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV), Ranking Member of the Energy and Natural Resources Committee, took to the Senate floor to discuss the Great American Outdoors Act (S.3422) before the Senate voted 80-17 to invoke cloture on the motion to proceed to consideration of the bill. A cloture vote ends the debate. It does not mean the bill has passed. At least one more process vote will be taken before final passage. The next vote should occur later this month. In March, Senators Manchin and Cory Gardner (R-CO) introduced this bipartisan legislation that provides mandatory permanent and full funding for the Land and Water Conservation Fund (LWCF) and addresses the $21 billion maintenance backlog in national parks and other federal land management agencies.

The GAOA is a very important bill and will benefit generations to come. This bill combines two major conservation bills: S. 500, aimed at reducing the nearly $20 billion deferred maintenance backlog on public lands, and S. 1081, which would make funding permanent for the Land and Water Conservation Fund at its $900 million annual authorized level. The Great American Outdoors Act is important for plant conservation because it contains language that requires native plants and natural infrastructure to be used in the projects funded by the bill.

Under the bill, the National Park Service would receive the bulk of the aid — 70% of the funds — or roughly $1.3 billion per year beginning in fiscal 2021.

The Forest Service and Fish and Wildlife Service each would get 10%, or $190 million annually, while the Bureau of Land Management and Bureau of Indian Education would each collect 5%, or about $95 million annually.

The Great American Outdoors Act is supported by many organizations across the country including the Garden Club of America, local businesses, the recreation industry, veterans’ groups, conservation organizations, tourism and travel associations, sportsmen, and infrastructure groups.

For more information, see Center for Plant Conservation Advocacy page.

The Center for Plant Conservation Advocacy Committee tracks federal legislation that have direct impact on the safeguarding of rare and endangered plants. Please stay tuned for developments. We may need your voice to save plants.

Learn MoreSan Diego Zoo Global Supports The Australian Network for Plant Conservation

San Diego Zoo Global is supporting The Australian Network for Plant Conservation and the plant conservation actions needed for post-wildfire recovery. Aligned with the recommendations of the Australian Federal Threatened Species Scientific Committee for Post-fire Recovery, the team will take actions to: 1) Prevent extinction and limit decline of native species and ecosystems affected by the 2019-20 fires, and 2) Reduce impacts from future fires. Specifically, partners will identify the narrow-range endemics and priority threatened plant species most sensitive to having recovery disrupted by repeated fires in the near future. Field inspections will quantify recovery and identify threats that need amelioration. Seed and/or vegetative germplasm will be collected and established at regional botanic gardens. Working with experts, land managers, indigenous consultants, and fire management authorities, the team will assess fire regimes and impacted plant species, and develop a document “Fire Regimes That Cause Biodiversity Decline.” They will design web tools to provide guidance on recovery actions and build the resilience of biota to future fires.

With funding support, local research scientists and contractual field scientists will conduct on the ground assessments that can inform the habitat-specific guidance plan. Promotional materials and web-based interactive tools will be created to guide community thinking and actions in post-fire landscape management. Draft strategies for at least 10 species will be developed to protect species from future fires and other threats during their sensitive recovery phases. SDZG Plant Conservation’s Sula Vanderplank will participate in discussions remotely and review strategy documents designed to reduce species’ extinction risk, especially in the face of future fires.

Conserving the Jewels of the Night: What Natural Areas Professionals Can Do to Help Fireflies

Abstract: Fireflies, lightning bugs, glow-worms—these are but a few of the names used to describe some of our most

celebrated insects. Fireflies have fascinated children and adults alike for centuries, and beyond their cultural, biological,

and economic importance to humans, they are also important components of natural ecosystems. Over 150 species have

been described from the US, ranging from the commonly encountered big dipper firefly in the East to the California pink

glow-worm in the West. Fireflies—including flashing fireflies, glow-worms, and daytime dark fireflies—use a wide range of

habitats, from riparian forests and desert canyons to tallgrass prairies, mangrove swamps, agricultural fields, and

numerous other places in between. And yet, like many insect species, they appear to be in decline. Although monitoring

programs are scarce, growing anecdotal reports, backed by expert opinion, suggest that firefly populations are in trouble.

Key threats to their persistence include habitat loss, light pollution, and pesticide use. By understanding these threats and

what fireflies need to thrive, natural areas professionals can play a significant role in their conservation. In this webinar,

we will provide an introduction to firefly life history, discuss some of the threats they face, and outline key steps that can

be taken to protect fireflies and their habitats in natural areas across the country.

Unlocking Boundaries: Propagating Native Plants with Incarcerated Populations

Presentations by Stacy Moore, Ecological Education Program Director, and Tyler Knapp, Ecological Education Coordinator, both at the Institute for Applied Ecology.

Buzzworthy: Conserving bumble bees in our natural areas

Native Plants, Green Roofs, and Low Impact Development is a free webinar that is being held on Saturday, June 13, between 3pm – 5pm CDT. Below is a description of what viewers can expect to learn about:

Homeowners are encouraged to attend this workshop to learn about how they can help protect local waterways by implementing low-impact development (LID) techniques on their properties. Jane Maginot, Water Quality Agent for Washington County (Arkansas), Lee Porter of Ozark Green Roofs, and Eric Fuselier of the Wild Ones (Ozark Chapter) will present on various methods and techniques that can be used to slow down, spread out, and soak in stormwater on-site, creating a more environmentally friendly place for wildlife while improving soil and protecting water quality. Additional topics to be discussed will include green roofs, rain gardens, and phytoremediation.

Pollinator Week: Pollinators, Plants, People, Planet

Pollinator Partnership is proud to announce that June 22-28, 2020 has been designated National Pollinator Week!

Thirteen years ago the U.S. Senate’s unanimous approval and designation of a week in June as “National Pollinator Week” marked a necessary step toward addressing the urgent issue of declining pollinator populations. Pollinator Week has now grown into an international celebration of the valuable ecosystem services provided by bees, birds, butterflies, bats and beetles.

Due to the current situation with COVID-19, Pollinator Week 2020 will not be a typical Pollinator Week. We urge everyone to hold a socially distant, appropriate event. In an effort to lighten the load on state governments during this time, we are not pursuing formal state proclamations this year, but will continue to post proclamations that we do receive. Moreover, we encourage everyone to go outside and spend some time with the bees and butterflies that inspire hope in many.

Learn MoreCongratulations to Dr. Naomi Fraga, Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden!

Dr. Fraga was named one of the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Pacific Southwest Region’s 2019 Recovery Champions!

The Botanical Research Institute of Texas to Begin Managing Fort Worth Botanic Garden

The Fort Worth City Council voted on Tuesday to turn over management of the Fort Worth Botanic Garden to the Botanical Research Institute of Texas (BRIT) for a 20-year term.

The benefits of the management agreement include: opportunity for significant growth, funding from broader sources, enhanced educational programs, professional fundraising and membership staff, cultivated donor base, and management of private funds.

Learn MoreWays to Help CPC

Support CPC by Using AmazonSmile

As many of us are now working from home and relying on home delivery more and more, we wanted to remind you that you can keep your home stocked AND SavePlants. If you plan to shop online, please consider using AmazonSmile.

AmazonSmile offers all of the same items, prices, and benefits of its sister website, Amazon.com, but with one distinct difference. When you shop on AmazonSmile, the AmazonSmile Foundation contributes 0.05 percent of eligible purchases to the charity of your choice. (Center for Plant Conservation).

There is no cost to charities or customers, and 100 percent of the donation generated from eligible purchases goes to the charity of your choice.

AmazonSmile is very simple to use—all you need is an Amazon account. On your first visit to the AmazonSmile site, you will be asked to log in to your Amazon account with existing username and password (you do not need a separate account for AmazonSmile). You will then be prompted to choose a charity to support. During future visits to the site, AmazonSmile will remember your charity and apply eligible purchases towards your total contribution—it is that easy!

If you do not have an Amazon account, you can create one on AmazonSmile.

Once you have selected Center for Plant Conservation as your charity, you are ready to start shopping. However, you must be logged into smile.amazon.com—donations will not be applied to purchases made on the Amazon.com main site or mobile app. It is also important to remember that not everything qualifies for AmazonSmile contributions.

So, stay safe inside, and when ordering online, remember you can still help save plants. Please feel free to share this email with your friends and family and ask them to select Center for Plant Conservation.

Thank you all for ALL you do.

Donate to CPC

Thank you for helping us save plant species facing extinction by making your gift to CPC through our secure donation portal!

Donate Today