Your State Rare Plant Data Centers – The Natural Heritage Network

Our natural heritage is the sum total of our biodiversity, ecosystems, and geological structures. More and more people are thinking about what this means to us. What have we inherited? What will we pass on to others? It’s essential that we know what we have in order to care for it and be able to pass it on. This knowledge is a key role of the Natural Heritage Programs that constitute the NatureServe Network, a group of primarily state-based public and private entities that gather, inventory, assess, and manage data on rare and threatened species and ecosystems in each state.

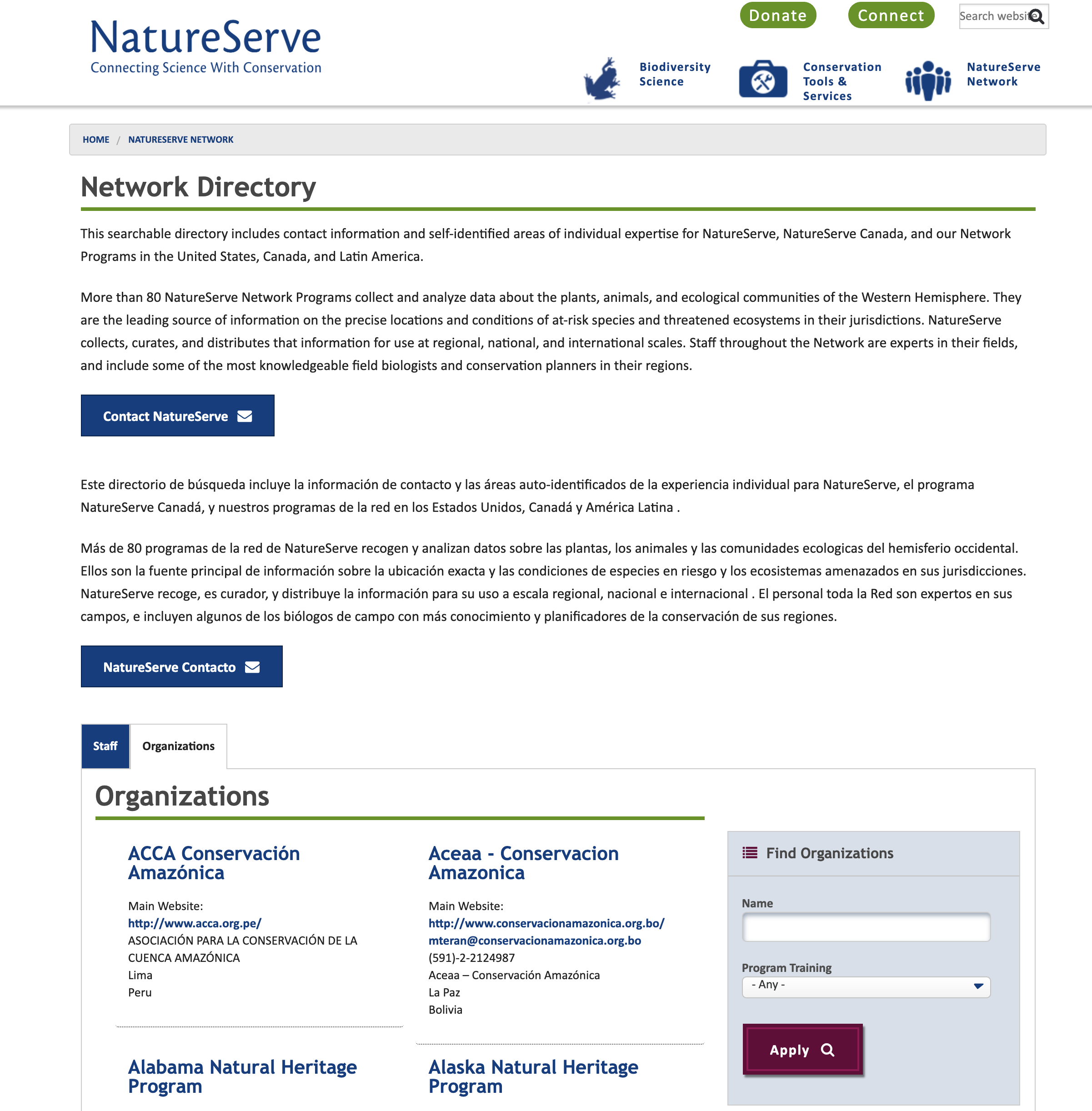

There are currently about 100 Natural Heritage Programs now, covering all 50 states, the Navajo Nation, Canada, and several Latin American and Caribbean countries. Many still carry the Natural Heritage Program name (e.g., the North Carolina Heritage Program), while others have been folded into government or university programs with different names and, in some cases, expanded roles (e.g., the Oregon Biodiversity Information Center). Most of the programs have at least one botanist. Keeping up-to-date with all the rare plants in their jurisdictions is a tall order, however. Tennessee’s Natural Heritage Botanist, David Lincicome, has stated that it would take 19 years to monitor and update all rare plant population records in the state! According to our June Conservation Champion, Anne Frances of NatureServe, “Programs are always interested in learning and documenting newly discovered rare plants and rare plant locations,” and the opportunities for partnership are vast. The data for these programs then feed into the NatureServe database and inform NatureServe’s status assessments (determinations of how rare or threatened the plants are).

In California, a state tracking more than 2,400 rare or threatened plant taxa, partnerships are key to data collection. The botanists of the California Natural Diversity Database (CNDDB) rarely collect their own data. Instead, a large part of their job is to help others to submit their data to CNDDB and to encourage them to collect additional information. According to CNDDB botanist Kristi Lazar, a big focus is on getting data on population size and threats. These are “two key pieces of information that are often lacking from data submissions” but are clearly important for assessing conservation status. CNDDB has collaborated with partners in data collection to develop an app that encourages more complete population reports aligned with CNDDB fields.

In New England, members of the Native Plant Trust (formerly the New England Wild Flower Society) work as part of the New England Plant Conservation Program (NEPCoP) to provide quality data to their Natural Heritage Partners. Through cooperative agreements, Heritage Programs in Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont share their data with the society. In turn, NEPCoP volunteers and staff update records by visiting known populations of rare plants and submitting their data for botanical inventories or new discoveries.

Getting current data on known populations has proven challenging in many places. In California, as with most states, the program is a key resource for people developing environmental impact reports and conducting research on particular species or habitats. Botanists conducting surveys for these projects use CNDDB data to visit a reference site (known location), familiarize themselves with the species, and determine appropriate timing for their surveys and research. Unfortunately, many of the botanists don’t think of this data interaction as a two-way street. They may consider this location to be already documented and not see a need to submit their updated observations to CNDDB. In reality, new data are vital for tracking long-term trends in known populations.

Understanding trends is critical for another vital function of Natural Heritage Programs—determining species’ state-level conservation status. These statuses correspond to the subnational status (S ranks) within NatureServe and may be tied to state-level protections. Here again, partnerships can be key. In California, the California Native Plant Society (CNPS, a CPC Participating Institution) takes the lead on assembling status reviews with staff from CNDDB, CNPS, and other experts to determine whether new species should be added or an existing species should change rank or be removed.

Similarly, NatureServe uses data from Natural Heritage Network programs and experts to review and improve the National and Global Ranks. Anne Frances states that they welcome expert feedback, expertise, and collaboration—particularly on imperiled species—and that CPC Participating Institutions have a lot to offer. She also believes that NatureServe’s aggregated dataset can help CPC identify species to be included in the National Collection and prioritize the species most in need of ex situ collections.

CPC institutions have built a variety of relationships with Natural Heritage Programs. Native Plant Trust has built relationships with the numerous programs in its region. Conversely, California, CNDDB works with numerous CPC institutions: history ties it closely with CNPS. CNDDB botanists rely on the excellent data generated by the California Botanic Garden (formerly Rancho Santa Ana Botanic Garden) and knowledgeable help from herbarium curators during checks. But no matter how the relationships are built, a state’s Heritage Program is an incredible resource for conservation.

In most states, the Heritage Program provides the only comprehensive dataset with a high standard for accuracy that covers the status and locations of rare plant species for that state. For example, California plant data are reviewed by two biologists for accuracy. Heritage programs work to become “one-stop shops” for rare species data by incorporating all data on each rare plant species, including field surveys, reports, collections, photos, etc. The high quality of the data make these databases important tools for conservation science and informed decision-making.

The Natural Heritage Network has proven itself worthy of its name, as an essential resource that strengthens our ability to pass our natural inheritance to future generations.